Goût

Taste has shaped my life since infancy. As I grew older, it became more important and now defines me as a chef. But what is taste, really? We all know it — yet few truly understand it.

In the cheese business, clarity matters. We must describe taste with precision and efficiency. We often talk about taste, flavor, and aroma when presenting cheese or speaking with clients. Yet simple words often fall short. Why? Because taste is complex. This article offers a short but deep dive into that complexity.

One note: I use “taste” to mean the full experience of food or drink. Flavor is only one part of that larger picture.

Taste perception forms in the gustatory cortex of the brain. Flavor, smell, nerve signals, nutrition, cross‑sensory effects, memory, and emotion all combine there. Together, they create a personal sense of how something tastes.

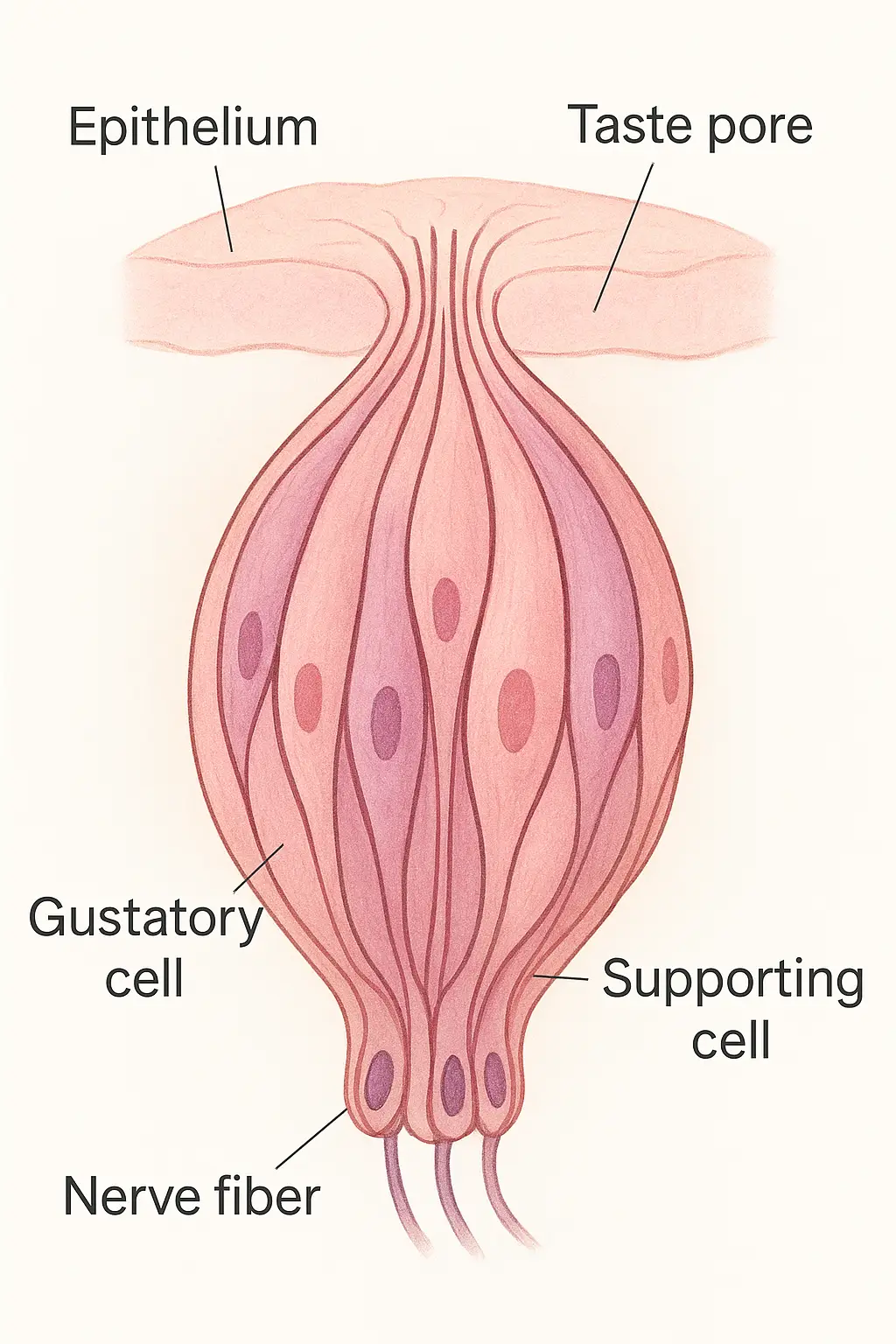

Flavor — Gustatory Input (Taste Buds)

Taste buds are regarded as tiny sensory organs that are found on the tongue, soft palate, pharynx, epiglottis, and upper esophagus. The five basic flavors — sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami — are detected by them. Within each taste bud, specialized receptor cells are contained, and responses to chemicals in food are carried out before signals are transmitted to the brain through cranial nerves.

Humans have an estimated 10,000 taste buds, mainly on the tongue but also on the roof, sides, and back of the mouth, as well as in the throat.

Taste buds work like tiny switches: they turn “on” when they detect a flavor molecule and stay “off” when they don’t. The strength of what we taste depends on how many of these switches are activated — a little sugar makes food mildly sweet, while more sugar makes it intensely sweet. Because taste buds only recognize five categories of flavor, they provide the foundation of taste.

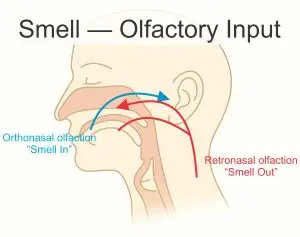

Smell — Olfactory Input

Smell is detected by olfactory sensory neurons located on the roof of the nasal cavity. The human olfactory system is believed to discern up to 1 trillion different aromas.

Quick Definitions:

- Olfactory epithelium: A thin layer of specialized tissue inside the nasal cavity containing sensory receptor cells that detect odors and send signals to the brain.

- Volatile compounds: Chemical substances that easily evaporate at normal temperatures, turning into vapor that can be detected by smell.

Orthonasal olfaction (“smell in”): The common method of smelling through the nose when inhaling odors from the environment — for example, enjoying the scent of a rose.

Retronasal olfaction (“smell out”): The process of smelling through the back of the nose, from inside the mouth. When chewing food, volatile aroma compounds are released and travel into the nasal cavity, stimulating olfactory receptors. This is the technique sommeliers use when slurping wine, and it also occurs when someone tastes food, swallows, and exhales before commenting on flavor.

Why They Smell Different

- Cognitive Framing: Orthonasal smells are treated as external objects, while retronasal smells are internal and thus perceived as more personal.

- Airflow & Compound Delivery: Retronasal airflow is slower and warmer, altering how volatile compounds reach the olfactory epithelium.

- Habituation: Orthonasal smell fades faster; retronasal persists longer during tasting.

- Neural Integration: Retronasal signals are more tightly linked with gustatory and somatosensory inputs, creating richer interpretations.

- Semantic Labeling: Orthonasal smells are often described abstractly (“grassy,” “chemical”), while retronasal smells are described in flavor terms (“nutty,” “creamy,” “spicy”).

Nerve Inputs — Somatosensory System

The somatosensory system, located in the parietal lobe, receives signals from skin, muscles, and joints. It contributes to taste perception through:

- Texture & Mouthfeel: Creamy, crunchy, gritty, rubbery, or smooth.

- Temperature: Cold vs. hot foods (ice cream vs. melted cheese).

- Pain & Irritation: Capsaicin in chili peppers creates “spicy heat.”

- Astringency: Wine or tea compounds cause a drying, puckering mouthfeel.

- Pressure & Movement: Chewing, biting, and sensing food’s physical presence.

This isn’t limited to sensory input from the mouth, throat, or nasal cavity. It could be the cold slipping into your ski jacket, or the slow burn of chili deep in your stomach.

A warm mug of hot chocolate cuts through that creeping chill — not just warming your hands, but reclaiming your whole body from the cold. That’s what makes it feel so special.

And that third spoonful of spicy curry? It hits differently. The first two have already begun warming your core, so by the third, your body is primed — the heat builds, not just in your mouth, but in your belly.

Crossmodal Influences

Our senses affect each other in complex ways. Visual, auditory, tactile, and emotional/cognitive inputs (feelings and memories) can dramatically shape taste perception.

Examples:

- The sand between your toes, the blue ocean, and the sound of surf at a seaside restaurant can influence how your grilled fish and coconut taste. It becomes part of the overall experience. By contrast, the same fish and coconut served from a street cart in a small, dark, dirty, and smelly alley in Beijing would carry a very different taste — one that aligns with the memory created in that setting.

- The cool breeze and birdsong in the green pine trees of your childhood mountain home, combined with the memory of your mother making cheese toast served with a fresh glass of milk, can bring back vivid memories of your youth. Those memories influence how cheese toast made with the same type of cheese your mother used would taste today, because the experience is shaped by the emotions and associations from your childhood.

Nutritional Value

The nutritional value of food directly influences taste perception because our bodies and brains are wired to detect and prefer nutrients that support survival.

Examples:

- Pregnant women often crave nutrient‑rich foods. Development from embryo to fetus requires balanced nutrition. As development progresses, the growing baby depends on a steady supply of essential nutrients to support healthy growth and organ formation.

- Amino acid‑rich foods such as cheese, meat, and fermented products are especially desirable. Because amino acids are essential for human health, our brains instinctively seek them out — which is why these foods are often craved.

Conclusion

This is how we decide what something tastes like. It’s not as simple as what I learned in grade school or even in university culinary classes, but it gives me insight into why I love cheese toast and Balinese lawar. They are more than just foods — they are part of who I am. Their taste brings not only enjoyment but also genuine joy.

Wishing you a life full of Delicious Memories that you can frequent often! Chris

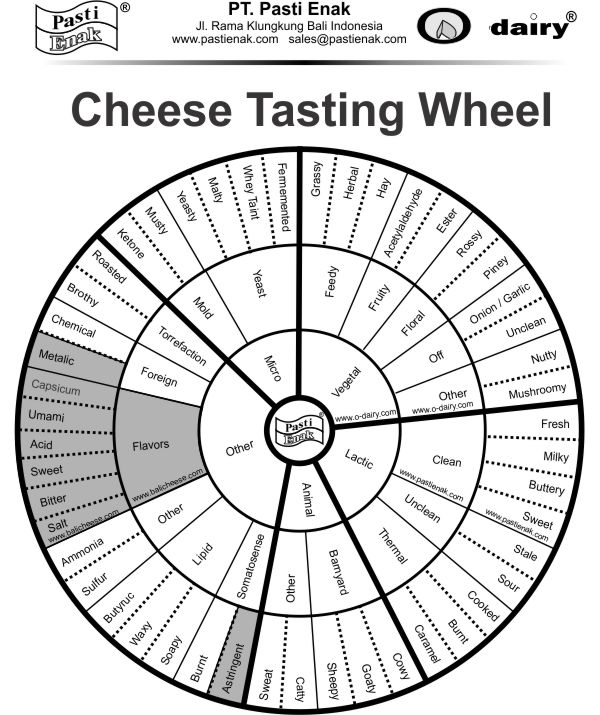

Our Pasti Enak cheese tasting wheel is a tool we use during tastings to help describe complex flavors. While some of the tastes listed on the wheel may seem undesirable on their own, many are part of everyday flavor experiences in very small amounts. Complex tastes are often created through a broad mix of flavors and aromas. This wheel helps break down those complexities into their individual components, allowing for a deeper appreciation of the cheese taste.